36. All Occasions Indeed Inform Against Them

The pandemic, AI, social media, teen hustle culture, the allure of inexpertise, dang interestin' country ya got there be a real shame if something awful and unsurprising happened to it...

As my first task as newly appointed Curriculum Czar, I call on 11th grade English teachers around the world to revamp their American Dream units. These units should be fluid anyway, not tethered to some long-antiquated understanding of the mythology. They should also give students insight into both the current prevailing and historically dominant versions of a fractured reflection, how we see ourselves at various points, not, of course, who we actually ever were or are as a country. The unit of the very near future cannot hinge on Gatsby, in other words—a story about a guy a long time ago who did all his cash-stacking and self-creation and fakery for an alarmingly superficial chick no less committed to climbing a (much shorter) ladder. It’s certainly not going to be The Nickel Boys or Solito—no, not any story about any sort of non-white person more recently running through some subverted version of the gauntlet.

The rags-to-riches, from nowhere-to-somewhere, from nobody-to-somebody. The worship of meritocracy and bold entrepreneurship and reinvention and belonging. America as a rich and ripe and verdant and messy canvas across which creativity can freely spill and flourish, regardless of the source’s circumstances of birth, and great ideas be born and swept away and born again.

These are all parts of the mythology that have been bent like an axle after repeated collisions. It might have always been a fairy tale but now it’s not even that.

I’d wager that more modern (white) teenage American boys than ever imagine this journey as impossible. A recent Pew poll didn’t survey teens, but 36% of all Americans between 18 and 29 characterize the Dream (whatever it means to them) as “out of reach.” Is that low or high? Faith in it certainly rises with each ascending age bracket. Does it continue to plummet before age 18? A 2024 Common Sense poll of teens between 12 and 17 saw nearly two-thirds of respondents state that “politicians and elected officials do not reflect the needs, desires, and experiences of young people.” White boys were slightly more convinced of this than other groups. A lot of my take though is anecdata that comes from teaching for 14 years at diverse schools and reading many pieces of writing and studying my own statistically suspect survey results—sorry. I’m pretty convinced that many of them—not clad in rags, already somewhere, convinced they’re not nobody—sense that this does not, in fact, favor them: a pure meritocracy in which inspiration and hard work can yield, for anyone, a piece of that pie.

In this line of thinking, they may buy some version of American Greatness in the way that you like your favorite team even when the new G.M. is messing up trades, but they don’t see that verdant field as a canvas they can fill as easily as they’d like. They are more likely to view the deck as stacked against them, even if, in their deepest hearts, it’s all a bit of an exercise, a sneering, willfully ignorant lark—to rebrand disenfranchisement as their undeserved burden. The sky is not falling but it’s not a bad game to play all the same. Sure, I teach plenty of affable white boys who are serious students with plans to study serious things and, for better or worse, follow a pretty conventional trajectory. The trend, however, is moving in a different direction, and it has been for several years.

This is why I was not shocked by those election results, which saw the former president, campaigning on darkness and incoherence, winning a greater portion of the under-30 vote than any Republican candidate since 2008. Young white men in particular further swung his way (+15% from 2020, according to AP data). I teach in a county in which only 18% of the population voted for the winner, but I do have some perspective on what might be percolating in the hearts and minds of American youth—even if, as I must point out, I’m quite aware that only a small portion of my students, affable white boys included, would count themselves as supporters of the 45th and 47th president.

Some of these plan to study business and join frats, which might put them in different and persuasive company. I perceive a somewhat understandable knee-jerk discomfort with movements that they’ve been told require them to shut up and accept fewer prospects in life. They get good grades, they participate in class, their parents make decent money, and the system works for them. They’re not interested in politics, probably because they’re socioeconomically privileged and don’t feel dramatically impacted by the consequences of elections. Very few want to write politics-focused editorials in Journalism or tie literary themes to contemporary political issues in Lit 11 or 12.

In contrast, the New American Dreamer, though, also white, but in my experience, increasingly, second- or third-generation Latino as well, thinks college is a total scam. School is disconnected from real life, namely the pursuit of money. They aren’t good at it anyway (in their minds). Social media influencers tell boys that they’re being systemically left behind, that women are swindling them and laughing at them, leaving them for taller guys with bigger muscles and superior financial prospects. Many boys chuckle at these messages but they get them anyway.

So, here’s my still-toasty take: plenty of these boys don’t want a level playing field, a fair chance to make it on merit when circumstances are uncertain. To put this in gamer terms, they don’t want to face challenging levels, negotiating twists and turns, building themselves up in the process. They just want a cheat code. They want easy mode. They want to be the main character, on top, in a nice car, in their own lane, zipping past the bystanders and losers who, for some reason, never got a cheat code of their own.

This is old, sure, the teenage desire to cut corners, but what’s new is they don’t even pay lip service to the old tenets of the Dream. They crave wealth but not necessarily a career, wanting often instead to prevail via hustle and conspicuously casual craft instead of labor, to ditch the costly college pathway that they already feel privileges the historically disadvantaged—the kids who take their spots at highly selective state schools. Who wants to pay $70,000 a year for a degree from Arizona State when you can have a hot car at 19 and work from anywhere in the world? They want crypto. They want to sleep while a bot does exchange trading on their behalf. They want to slide into the optimal rungs of multi-level marketing schemes. Plenty may even go to college but that’s as much for social opportunities as employment prospects, and definitely not any notion of becoming literate or wise. As Jamelle Bouie recently wrote on Bluesky, they, like older Americans, “have responded to the precarity of the modern economic order by embracing values of entrepreneurism and individual ‘hustle’ that Trump reflects back to them.”

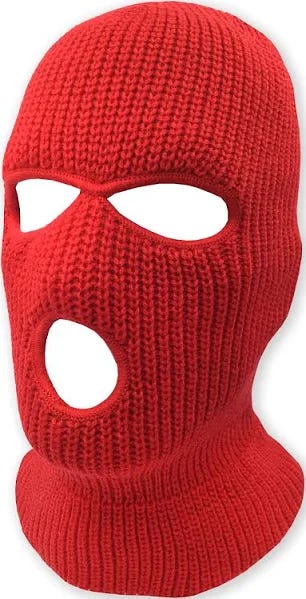

This archetype finds the message—conveyed with rage and humor—appealing. They may be angry but they for the most part aren’t desperate, trying to scrape out a living amid the “carnage” that Trump invoked at his first inauguration. Are they really mad about eggs being costlier? Nonetheless, costuming themselves in the garb of hopelessness suits their narrative. Many are underdogs with relatively silvery spoons clutched between their jaws. Even many of the poorer kids I teach often have bedazzled iPhones, vanity-plated cars of their own, and expensive belts—material comforts balanced by a vague sense that the future has already left them behind. In this Dream, you can have treats and nothing at the same time.

The New American Dream is animated by grievance, not hope, by cold capitalist calculations, not romance, by the embrace of inflexible hierarchies, not the dismantling of them. To return to literature, Gatsby is a hustler committed to extra-legal economies, which makes him cool, but he’s also a romantic, and he’s a failure, which makes him a loser (getting rich to hack status prove himself worthy of the pretty girl who wouldn’t commit to him anyway)—unlike the Tateian disciple who turns romantic rejection and insecurity into bitterness, whose goal is to crush and subjugate and manipulate women, not adore them. Gatsby, who does adore, is in the end as controlling as Tom Buchanan—a fabulously wealthy and unemployed MAGA type who might scoff at the bad manners of bigoted peasants while being similarly terrified of some overturning of the accepted order by immigrants or people of color or, in our current time, the most fashionable demon: trans youth run amok. Can’t you see Tom spending his tipsy, bored afternoons issuing Truth Social rants about whatever outrage Tucker has most recently served up?

I’d wager that, despite their interest in hustle culture, more teenage boys in 2024 identify with Tom—an imposing ex-athlete and perpetual philanderer who simply is power and wealth—than Gatsby, who wears a strawberry ice cream suit and plays mortifying make-believe. Tom does not have a job. He looks down on the idea of work. He, though an Ivy Leaguer, clearly knows nothing about the intricacies of the finance world in which Nick has immersed himself—Nick being an old classmate, a conventionally privileged plodder in the American economy. Tom clearly got the cheat code at birth. He is an elite who lives luxuriously and, while Gatsby dies, Tom suffers no lasting consequences for hurting people. The New American Dreamers do not resent elites at all. They aren’t punk or anti-establishment. They just prefer some to others: the macho business world-beaters who were born wealthy and flashy tech overlords (also often born wealthy) over the academics, scientists, lawyers, and so on— anyone who expects a self-styled “smart person” to have actual expertise and value the effort needed to gain it.

Being like Tom sucks. America should have fewer Toms. Fitzgerald has contempt for him. That’s part of the message, a commentary readers for decades have perceived. What made Tom Buchanan revolting to my own English class in 1997 (a Kentucky private school with no shortage of conservative students) makes him more appealing today.

Not because he hits women or cheats. More because he gets away with it, whatever it happens to be. Thanks to a steady diet of toxic social media influencers, boys in America are more susceptible than ever to this stance.

But this character I share, a New American Dreamer, a construction springing from my experience and observation, doesn't really do the reading anyway.

Caught plagiarizing, routinely tardy or absent without excuse, his grade plummeting towards the teens percentage-wise, the New American Dreamer still approaches his teacher to boldly self-advocate. He’s been taking challenging classes (he hasn’t) and wants you to excuse what he hasn’t done—you understand, don’t you? He apologizes for using AI for a writing assignment but then, instead of doing a full rewrite, proceeds to make cursory edits to the AI “original.” I’m really trying to get that B, he tells you, ignoring your point that, if that had been a priority, he’d have made a different choice. He asks you to do the math. Will he get that B? Can you say he will? He wants to make a deal and hold you to it. The same Dreamer blows a thousand lay-ups over the course of a basketball season but brags about his two dunks. You get the idea.

The New American Dreamer writes, for an open letter assignment, that people “nowadays” are too sensitive, but at the end of a quarter, he calls upon a teacher’s sensitivity when he’s a few points shy of soccer eligibility. Feelings aren’t feminine or weak when they’re reserved for him. The New American Dreamer either raises his hand and talks too much about little or slouches in the back of class, nudging open his laptop to surreptitiously study baseball highlights. But the New American Dreamer also avoids confrontation and debate. If called out, he wilts or shrugs.

The New American Dreamer, who does low-level sports gambling with his friends, is in no danger of becoming a billionaire but identifies as one all the same, explaining in a survey response that billionaires should get to do “anything” with their money. Really, anything? Anything? Hunt people for sport? Buy a job in government and self-enrich further while tearing a country down to the studs? The New American Dreamer valorizes wealth, not morality or service, tech, not science, business instead of economics. The New American Dreamer sees his potential reflected back in the successes of his idols. Be deviant, ruthless, aggressive, eccentric—that’s how you slide through the bars to a life of pure freedom. They believe in the Dream after all. They just define it differently.

***

This is where we are, I’m thinking. The examples are real and entirely unexceptional. So, how did things get to this point?

To take a stab at this question, considering only the slim portion of the electorate I know well, I think we need to go back to a sunnier time in American history: the first full year of the Covid-19 pandemic!

When school buildings shuttered in March 2020, students received a very important message that has since stayed with them into their early adult years: school does not matter. I don’t say this as someone who thinks these closures were wrong. They could have partially ended with tent schools and other creative measures to reduce viral transmission and allow for some face-to-face interactions by August of the same year. The typical absence of nimble solutions aside, the problem—at least with my school—was that administrators were so (fairly) concerned about students coping with the sudden upsetting change to their lives that they (stupidly) dramatically reduced academic and attendance expectations with nearly two months left in the year. Like other teachers, I transferred everything online and hammed it up in the Zooms but enthusiasm and care dwindled almost immediately after the school announced that failure was impossible. The policy was not the problem, just the proclamation. The understanding of education as option as opposed to necessity carried over into the subsequent year and beyond—with rising chronic absenteeism, an increase in inappropriate social behaviors at school, a reduced capacity to complete projects, a diminished attention span required for reading and problem-solving, and more. Students could miss class and do nothing and, even as they fell behind, not quite believe the parade of readings and discussions and assignments was really happening on an alternate plane.

When you stop seeing and then believing in consequences for behaviors, even as those consequences land on your head, when you decide to let the institution that once most shaped you outside of your home crumble and fade, you’re open to other institutions that govern the adult world crumbling, and, relieved, elated, simply seeking entertainment, you might even hasten that process—a dynamic that Elle Reeve captures in the excellent book Black Pill. You’re generally more comfortable making lots of choices big and small without regard for consequences. A vote is one such choice.

School between March 2020 and, in my case, April 2021, was also like the Internet—the axis around which hustle culture spins, the place to be if you’re into scams or inauthenticity or making choices without regard for consequences. School unfolded on the Internet, yes—Zoom, an app I still dread using even for family summits or guest speakers, Canvas, a multitude of largely unhelpful apps and platforms, some of them, like Flipgrid, in design, intentionally mimicking the platforms students already used for socializing. We have known for a while that screens were bad for kids, but now they were tethered to them for nearly any nonathletic purpose. They played video games, interacted with friends, and did all of their academic work on screens. The anonymous, detached, caustic, attention-seeking, casual behaviors common online bled into class. A girl, for example, made a TikTok commenting on the facial expressions of students in the Flipgrid responses they made for a chapter assignment. “Likes” made it clear who was popular and who was ignored. Another girl made a TikTok about teachers she would date. These particular kids faced consequences, but it was also not unusual, in a daily sense, to see blatant on-screen multitasking or rows of black rectangles instead of attentive and semi-engaged faces—the faces of young people fighting for their right to learn amid crisis. “Huh?” one kid once bellowed when I asked him a question. His camera accidentally turned on, pointed up towards his face at a warped Third Man-y angle, and he was staring off to the right at, presumably, another screen. I repeated my question. He turned off his camera and didn’t respond. That was it! “Turning your camera off” became and remains a powerful trope. With this choice, you leave the community to which you are welcomed, one that depends on your presence, and signal that you have no responsibility to contribute or desire to be supported.

If America fears the voting choices of an aloof, low-information, conspiracy-hungry populace, irrevocably merging school and the Internet was a step in the wrong direction. Students retreated into their comforting online worlds, found influencers, streamers, and subcultures that appealed to them, and reemerged, less confident, quieter, less socially adept, more comfortable being physically present while mentally somewhere else, and, undoubtedly, more transparently cynical about the value of learning and belonging to a real community.

The AI boom first hit later, in 2022, but the timing was terrible. Just as kids were regaining a bit of footing, tentatively reconnecting in the second full “post”-pandemic year, they received a new tech tool that encouraged further detachment and cynicism but added a new ingredient: arrogance!

Ah, the staff of life.

As many have written, generative AI can simulate knowledge or a work product well enough for a kid who is not very capable (sorry) to feel as if real knowledge and work products don’t count for much. Imagine the job interviews of 2030, my former New American Dreamers with invisible earpieces, tapping codes under a table into smart watches that are recording the interviewer’s questions.

“Did you hear me? I asked if—”

“Yes, I heard, I’m just…”

(...waiting for the robo-homie Wintermute to stage-whisper through the earpiece an impassioned ready-made monologue about a commitment to service and collaboration being lodestars of a productive workplace…)

The future will be more Idiocracy via William Gibson than a bonnet-free Handmaid’s Tale but enough of both, I suspect. If you’re already a bit behind academically, this cheat code makes you feel smart and eventually you can convince yourself that you are. Hustle culture gets a brand new bag with AI. Superficial academic success via the simulation of expertise is a greater honor than achievement through effort and care. I have straight up had students admit this: intelligence gets defined by how easily you avoid showing knowledge, curiosity, critical thinking, and creativity. If a tech overlord is not, in fact, a gifted coder, that is all the more reason to admire him. Break a campaign promise? Sell out some friends? Suckers shouldn’t have been suckers.

I did notice during the online year away from my classroom that kids were working more than before. Employers eagerly offered more hours to high school students, who didn’t mind schedules conflicting with class meeting times. Families were making do with less money coming in, and my students who elected to work full-time were doing so out of a sense of obligation, a desire to exert power over tumultuous and uncertain circumstances. The year was a crash course in vulnerability and helplessness. Target was still there. Time had to be spent. Money was real, deposited into their accounts every other week. What was happening over Zoom, in breakout rooms, over Canvas—all that felt far less real, totally irrelevant (not that they were right). One kid told me over the phone that he would worry about his G.E.D. later, that he was going to be a mechanic with his uncle. A boy I'd taught as a ninth grader, now a senior, explained his decision quite rationally. He would work 40 hours a week, and do what he could to pass, but otherwise place school, no longer a location but a concept, on a distant back-burner. Failure was so unlikely given the new grading and attendance policies that he figured his gamble would succeed. He’d squeak by, do summer school and/or community college, and transfer to Berkeley down the road. Things might have worked out for him (I don’t remember), but he contributed nothing to my class, learned nothing from the opportunities he was offered, and further helped reduce the meaning of an institution and the experience it provides. He, at best, hustled.

***

I don’t mean to be so negative. I simply have nothing but contempt for any young person who votes on the basis of hate or fear of women, trans people, immigrants, or other minority groups. I can’t respect anyone of any age who votes or plans to vote out of a desire to see cultural adversaries and their families punished. Even as I try not to be that teacher, I can’t help but point out the hypocrisy of anyone wanting a nanny state for themselves and strongman authoritarianism for others. But I don’t care if students hate taxes or think that the government is bloated or roll their eyes at the oft-empty celebrations of diversity they witness. Groups are not monolithic and no party is entitled to anyone’s vote. I think American voters made a grievously stupid decision on the basis of baseline competence and stability alone. I think the young people who will someday say they voted this way for one reasonable reason (…shit is, like, expensive after a global pandemic…) and not the others (deport, dissolve, denigrate, etc) are wrong. They bought the ticket and deserve the whole ride. But I don’t teach with any partisan political mission in mind—definitely not cheering the administration that, for all of its incrementally beneficial efforts on behalf of working people, has been, for a year, sending money to a government committed to killing children.

I grew up with what I sensed was a grandfatherly Greatest Generation conservatism in the 80s and 90s—condescending, dusty, well-mannered in public, out-of-touch. In 2016, Trump reminded me a bit of a private high school friend’s prototypically racist dad—a Boomer, gregarious but coarse, funny but ugly. You wouldn’t ever feel comfortable around him. You would never imagine seeing things the way he did. But he would monologue in the living room with a whiskey in one hand while you sat and hoped he didn’t know how baked you were. He’d do something generous and improvised—like bust out a box of Cuban cigars and toss you one. He’d be big, wearing a polo, fresh from drinks with golf friends. He’d hold court and tell a few normal jokes. You’d chuckle. He’d tell you about seeing Zeppelin in 1973 and absentmindedly swaddle his ancient dog in a blanket and endearingly rock it like a baby as he yapped. Then he’d do the one about driving so fast down the boulevard by the park that he’d knock the yarmulkes off the heads of anyone crossing the street to go to synagogue. He’d show his teeth. Spit out a sudden rant about nonexistent area crime and the skin color of the people he knew to be responsible. You’d want to leave, toss the Cuban out the window, but still, on some level, when you thought of him later, as an impressionable teen, as much as you didn’t like him (a guy who obviously loved to be liked) or see the world this way, you wanted him, an alpha with a sprawling house and a nice car and no interest in accommodating anyone, to like you.

I think on some level, this explains a lot: why more vulnerable teen boys and young adult men are fans, even by default. Last year, I watched my teacher neighbor across the hall ask a Latino student with whom he often good-naturedly bantered why he liked Trump so much.

“Everything,” I heard the kid reply, a big grin splitting his face.

The teacher asked him to name a policy he especially believed in, something concrete.

“All of it,” the kid said. “Everything.”

Name one single policy and explain why you like it, the teacher said.

The kid laughed and walked down the hallway. Camera off, black rectangle time.

Even among the affable studious teen boys, it’s not cool to proudly say you identify as “liberal.” It doesn’t come with swagger. Being a liberal is, for lack of a more appropriate term, bitch-coded. The friend’s perpetually tired-looking mom coming downstairs, a book under arm, telling your friend’s dad that it is entirely inappropriate to give cigars to 16-year-olds. And getting ignored. The girl in class who has always done the reading and keeps making points in discussion that your warm but sarcastic specs-wearing teacher seems to think are brilliant. It’s about following rules and holding things together. After the last five years, it’s much easier and more fun to tell the nags and moralizers to fuck off and yank things apart.

Maybe “radical” will fare better in the elections to come.

I feel pretty sympathetic to the cohort of teenagers and young adults who have been buffeted by the pandemic and resulting global economic downturn and intentionally intoxicated, stifled, and warped by addictive technology, the soundsystem for the algorithmically advantaged worst ideas in the world.

Maybe all occasions indeed inform against them after all!

Education is not solely the responsibility of schools, but I can still hope that, over time, an increased curricular emphasis on media literacy, meaningful and authentic community-building exercises at school, and dramatic reductions to screen time at home and in classrooms can make building things together attractive again. I’ve been very down on teaching lately, and if there’s a thin personal silver lining to this next American phase, it’s that I feel a renewed need to invest my energy in the health of the country. I don’t want to cash in my chips as much as I did last year. If the New American Dream is here to stay, at least for a while, it’s invigorating to bear some responsibility for resisting it, for offering another way, for gently or aggressively as the situation fits defining and celebrating paths to a healthier model.

And I can be hopeful that, if more people try, they can be good people regardless of the tax plans they prefer, believers in democracy, seekers of truths, not knee-jerk nihilists who live and vote to spite or scoff or be entertained. Maybe broadly committed to human rights and justice? That asking too much? The pendulum swings so long as it’s allowed to; political winds change. You have to live with yourself until you die.

I’m doing a promising project right now with Lit 12, and I plan on discussing the whole unit in detail next month, once it’s further along and the project results are more apparent, but this too gives me hope. The project, in short, involves students conducting highly focused self-directed inquiries and presenting solutions-oriented arguments regarding dystopian consequences of technology for a semester-ending conference. Without prodding from me, kid after kid is addressing some aspect of social media and teen mental health—so many that I may need to make a few change their topics. Several are studying the influence of AI on education. A surprising number are interested in all manner of influencer-fueled scams. Giving students the opportunity to thoroughly investigate the sources or at least the sound system for what ails them might be a good enough beginning.

See you in the halls.